What Weather Really Takes Away: The Hidden Meaning Behind Those Umbrellas on Power Lines

After Hurricane Katrina, shoes appeared on telephone poles in New Orleans. Not scattered by the wind, but deliberately placed—a pair here, a single sneaker there, hanging like odd fruit against the sky. In Japan, after the 2011 tsunami, origami cranes began covering fence posts in affected areas. In Puerto Rico, following Hurricane Maria, colorful ribbons materialized on power lines throughout devastated neighborhoods.

And now, in countless communities worldwide, umbrellas are appearing on power lines after storms pass. Red, blue, yellow—carefully positioned like strange flowers blooming in the aftermath of destruction.

This isn't vandalism. This is the raw vocabulary of trauma, spoken in a language older than words.

When Words Fail, Objects Speak

Trauma has a way of strangling language. When entire communities are devastated—when the familiar becomes foreign, when safety dissolves with the storm surge—traditional forms of expression often feel inadequate. How do you capture the weight of losing everything in a Facebook post? How do you condense the experience of watching your neighborhood disappear into a text message?

You don't. Instead, you hang an umbrella on a power line.

Dr. Sarah Chen, who studies community responses to natural disasters at UC Berkeley, explains: "These spontaneous installations serve as a form of collective testimony. They're visible, visceral reminders that something profound happened here. That we were here. That we survived."

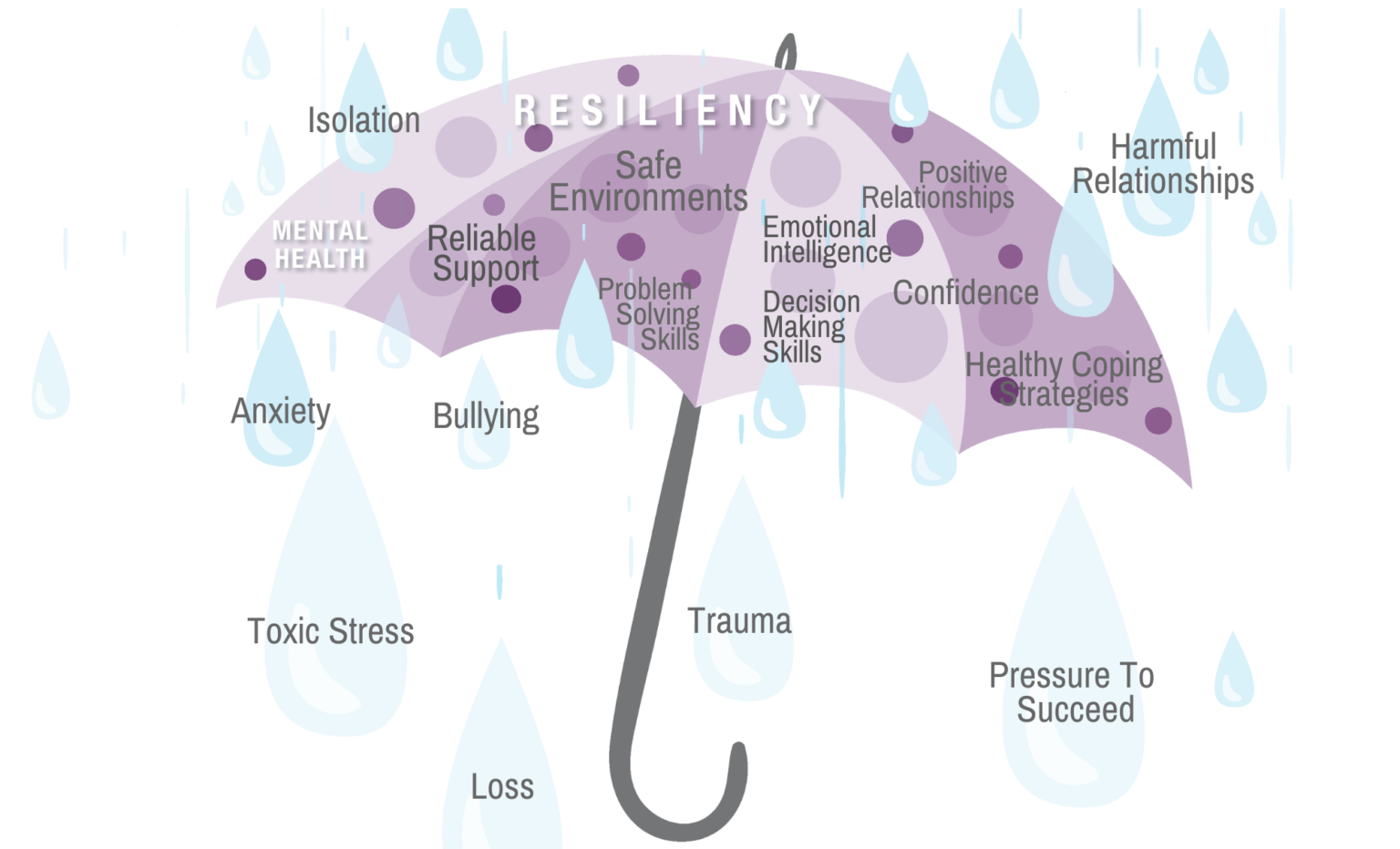

The umbrella—universal symbol of protection—becomes a paradox when suspended helplessly in the air. It's shelter that couldn't shelter, protection that failed to protect. Yet in that failure, it transforms into something else entirely: a marker of resilience, a flag of endurance.

The Ritual of Placement

"It's how we mark what the weather took away," someone said about those post-storm umbrellas. But what exactly did it take?

The obvious answer is material: homes, cars, photographs, heirlooms. But storms steal more than possessions. They rob communities of their sense of invulnerability, their assumptions about normalcy, their faith in permanence.

The act of placing an umbrella on a power line—requiring ladders, coordination, risk—becomes a ritual of reclamation. It says: We are still here. We still have agency. We can still create beauty from wreckage.

Urban anthropologist Marcus Rodriguez has documented similar phenomena across dozens of disaster sites. "These installations appear spontaneously, without central organization," he notes. "Yet they follow remarkably similar patterns. There's an almost archetypal quality to how communities process collective trauma through object placement."

The Democracy of Grief

What makes these improvised memorials so powerful is their accessibility. Anyone can participate. An umbrella costs five dollars at a convenience store. No special skills, artistic training, or permits required. No committees or approvals needed.

This democratic nature stands in stark contrast to official disaster response—the bureaucratic machinery of FEMA forms, insurance claims, and government aid. While institutions debate and deliberate, communities create. While officials measure and assess, neighbors memorialize.

The umbrellas don't solve anything practical. They won't rebuild homes or restore power. But they solve something arguably more important: the human need to transform suffering into meaning, to make the invisible visible, to turn individual pain into collective acknowledgment.

Beyond the Storm

These installations rarely last long. Weather fades them, authorities remove them, time erodes their relevance. But their temporary nature is precisely the point. They're not meant to be permanent monuments but living expressions of a moment—snapshots of a community's psyche in the aftermath of catastrophe.

Some residents embrace the umbrellas as symbols of hope and unity. Others see them as eyesores or safety hazards. City officials typically view them as code violations. This tension itself becomes part of the artwork's meaning—a reflection of how communities struggle to process trauma while maintaining the appearance of normalcy.

The Next Storm

Climate change ensures that severe weather events will become more frequent and intense. Which means these informal rituals of grief and resilience will likely become more common too. The language of collective trauma is evolving, adapting to our new reality of perpetual recovery.

The umbrellas hanging from power lines aren't just marking what the weather took away—they're marking what we're learning to live with. The recognition that safety is temporary, that protection is imperfect, that community is what remains when everything else washes away.

In that recognition, there's something approaching wisdom. And in the simple act of hanging a bright umbrella against a gray sky, there's something approaching hope.

Something that looks, from a distance, like strange flowers blooming in the wreckage of our assumptions about how the world works. Something that says: We were here. We endured. We transformed our breaking into something beautiful.

The storm took everything. But it couldn't take that.